Tutorial

Contents

Table of Contents

Lesson 1 Starting Up • The Mops Window • The ENTER Key

Lesson 2 The Stack • Stack Arithmetic

Lesson 3 Stack Notation • Arithmetic Operators • Mastering Postfix Notation

! Lesson 4 ! [Chapter4.html Mops and OOP] • [Chapter4.html#Inheritance Methods and Inheritance] • [Chapter4.html#Messages Objects and Messages] |- ! Lesson 5 ! [Chapter5.html Mapping Class-Object Relationships] • [Chapter5.htm #DefiningClass Defining a Class] |- ! Lesson 6 ! [Chapter6.html Objects and Their Messages] • [Chapter6.html#Summary Summary] |- ! Lesson 7 ! [Chapter7.html Modifying a Program] |- ! Lesson 8 ! [Chapter8.html Introducing QuickEdit] |- ! Lesson 9 ! [Chapter9.html Predefined Classes] • [Chapter9.html#Structure Data Structure Classes] • [Chapter9.html#OtherClasses Other Predefined Classes] |- ! Lesson 10 ! [Chapter10.html Defining New Words] • [Chapter10.html#ReturnStack The Return Stack] • [Chapter10.html#NamedInput Named Input Parameters] • [Chapter10.html#LocalVariables Local Variables]|- ! Lesson 11 ! [Chapter11.html Specialized Operations] • [Chapter11.html#Text Displaying Text] • [Chapter11.html#Stack Explicit Stack Manipulations] |- ! Lesson 12 ! [Chapter12.html Conditionals] • [Chapter12.html#Alternatives Two Alternatives] • [Chapter12.html#Truths Truths, Falsehoods, and Comparisons] • [Chapter12.html#Nested Nested Decisions] • [Chapter12.html#Logicals Logical Operators] • [Chapter12.html#CASE The CASE Decision] |- ! Lesson 13 ! [Chapter13.html Loops] • [Chapter13.html#Definite Definite Loops] • [Chapter13.html#Nested Nested Loops] • [Chapter13.html#Abort Abort Loop] • [Chapter13.html#Indefinite Indefinite Loops] • [Chapter13.html#EXIT EXIT] |- ! Lesson 14 ! [Chapter14.html Fixed-Point Arithmetic] • [Chapter14.html#Decimal Decimal, Hex, and Binary Arithmetic] • [Chapter14.html#Signed Signed and Unsigned Numbers] • [Chapter14.html#ASCII ASCII] |- ! Lesson 15 ! [Chapter15.html Global Values] |- ! Lesson 16 ! [Chapter16.html Sine Table Demo] • [Chapter16.html#Building Building a Sine Table] • [Chapter16.html#Works How the Sine Table Works] • [Chapter16.html#WhatHappens What Happens On the Stack] |- ! Lesson 17 ! [Chapter17.html Building a Turtle Graphics Program] • [Chapter17.html#Experimenting Experimenting With Turtle] |- ! Lesson 18 ! [Chapter18.html Create a Mini-Logo Language] • [Chapter18.html#Designing Designing the language] • [Chapter18.html#Implementing Implementing a Logo-like language] |- ! Lesson 19 ! [Chapter19.html Inside the GrDemo] • [Chapter19.html#Views Views] • [Chapter19.html#Positioning Positioning Views] • [Chapter19.html#Method Drawing Views-the DRAW: method] |- ! Lesson 20 ! [Chapter20.html Windows] • [Chapter20.html#Window The grDemo Window] • [Chapter20.html#dWind dWind] • [Chapter20.html#Controls Controls] • [Chapter20.html#GrDemo GrDemo Controls] • [Chapter20.html#Actions Scroll Bar Actions] |- ! Lesson 21 ! [Chapter21.html Menus] • [Chapter21.html#Running Running the Program] • [Chapter21.html#Summary In Summary] |- ! nowrap="nowrap" | Lesson 22 ! [Chapter22.html Installing an Application] • [Chapter22.html#FromHere Where To Go From Here] |}

Before we begin

You can compile a floating-point enabled version of either Mops.dic or PowerMops simply by loading the appropriate source file and saving the result, normally as a different program. In this manual we refer to such floating versions as MopsFP.dic and PowerMopsFP. The source files are, reasonably enough, named ‘floating point’ for Mops-68K, located in the System source subfolder of the Mops source folder, and ‘zfloating point’ for PowerMops in the PPC source subfolder.

In case you can't ‘intuit’ your way after a little exploration of the Mops window, instructions for compiling source and saving the results are given a little farther on.

Caution: In all the following keyboard examples, Mops commands are always terminated by <enter>, and <enter> is not the same as <return>. Many Mac applications treat these two keys as equivalent, but Mops doesn't. Once you've used Mops for a while you'll come to appreciate the usefulness of this feature.

Backup

We can't emphasize enough the importance of backup. Assuming you are using a hard disk, you should keep it regularly backed up. With programming, especially, system crashes are commonplace! But these shouldn't worry you, if your disk is regularly backed up.

It would also be good to keep an extra backup of the original Mops distribution, whether it was on disk or downloaded from the internet. Then, if you somehow destroy anything in the Mops system, you can easily get back to a working system, without having to download everything again.

Using an editor

Mops does not have a built-in editor, but works in close cooperation with QuickEdit, which was developed by Doug Hoffman especially for Mops, and is included here in the ‘QuickEdit ƒâ€™ folder. If both Mops and QE are running, they communicate via Apple Events to perform a number of useful functions. From Mops, you can ask QE to open a particular source file, and this will also happen automatically when an error occurs. From QE, you can send text to be interpreted by Mops, or request that Mops locate a source file which QE then opens. QE also incorporates an online Mops glossary. So we do recommend you give QE a try.

To use the online glossary in QE, just highlight a word, and choose Glossary under the Mops menu, or hit command-Y. Also, in the Glossary window, if you start typing the name of the word you want to look up, you'll be taken there. You'll find further instructions for using QE in the Readme file in the ‘QuickEdit ƒâ€™ folder.

In addition, QE is a proper standalone source-text editor for Mops programs.

Mops—an object oriented language

In Mops, much programming is done by sending messages to objects. A Mops object can be a simulation of any real-world object you're familiar with: a rectangle, a Macintosh window, an artist's canvas, a bank account. When a Mops program runs, a relatively small list of instructions route program execution through the framework of objects, and the objects come to life: a rectangle draws itself on the screen; a window appears; a mouse-controlled brush paints on an artist's canvas; a bank account monitors income and payments.

Mops, itself, includes many predefined types of object. With this preexisting framework, you can create complex objects as simply as typing two words. Let's do that right now, so you can get a taste of what Mops has in store for you. This is just a demonstration, not a lesson. So type (or copy & paste) along with us and observe what happens without trying to remember each step.

(Although there is a Mops-68K, comprised of the Mops and Mops.dic files, as well as the PPC-native PowerMops, it doesn't matter which application you use. Procedurally they are virtually identical. The principal difference is that to invoke Mops-68K you doubleclick on the Mops.dic file. Everything we say here applies as well to both.)

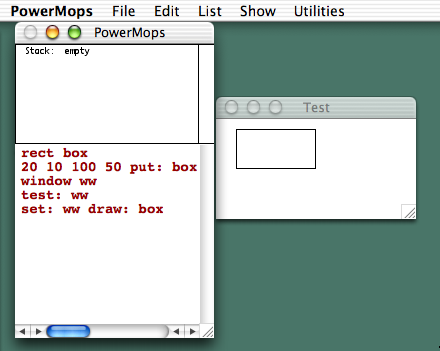

Open the Mops ƒ folder. Locate the Mops.dic icon and doubleclick it. In a moment, the Mops window appears. We'll explain the window's contents in detail in Lesson 1, but for now, create a rectangle object—called ‘box’—in memory by typing:

rect box

(Remember to hit <enter> at the end.)

We need to tell box where on the screen it should appear, and how big it should be. The rectangle framework inside Mops wants these instructions in the form of screen coordinates for two opposite corners, the top left and bottom right. We'll choose 20, 10 for the top left, and 200, 100 for the bottom right. Put these figures into box's memory by typing the following line, making sure you observe the spacing between elements and the colon:

20 10 100 50 put: box

This line is called a message, which we just sent to box. Now we want to send messages to box so that it will draw itself on the screen. First, however, it will need a window to draw itself in. To set up a window object—named ‘ww’—in memory, type:

window ww

Macintosh windows need a lot of information before they can be placed on the screen, including the rectangular limits of the window, the title of the window, the type of window, whether it is to be visible, and whether it has a close box. Even then, the Macintosh Toolbox requires much more information, which Mops automatically supplies. Some of the Mops classes, including Window, have test or example methods that display an instance of that class, with typical values. To see the window you just created, type the following message:

test: ww

|

Your screen should now look something like this: Actually, I cheated by select-and-dragging the instructions from the browser. |

You will be able to resize and drag ww around the screen as for any Mac window. But if you type keys while ww is in front, nothing will happen—this is simply because we haven't told ww what to do with keys. So move ww out of the way, and click on the Mops window so you can type further commands. Resize the Mops window if necessary so that ww is still visible.

Now type:

set: ww draw: box

|

The message 'set: ww' tells the system that drawing is now to take place in ww (but without bringing it to the front). Box should now appear in ww, and your screen should look something like this (of course you might have put ww in a different place): (We have shrunk the window's width to expose the background box.) |

When you are finished experimenting, select Quit from the File menu, or type

bye

in the Mops window to quit Mops

Now let's move on with the Tutorial, and I hope you find you enjoy Mops.