Difference between revisions of "Lesson 4"

m (wikification of headers) |

m (3 revisions) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

[[Image:InheritMethod.png]] | [[Image:InheritMethod.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | {| width="90%" align="center" | ||

| + | | width="33%" | [[Lesson 3]] | ||

| + | | width="33%" align="center" | [[Tutorial]] | ||

| + | | width="33%" align="right" | [[Lesson 5]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | colspan="3" align="center" | [[Documentation]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

Latest revision as of 04:41, 1 January 2009

Mops and OOP

Armed with a basic knowledge of Mops' stack, you're now ready for an introduction to the language's real power; its OOP (Object-Oriented Programming) nature.

OOP is such a popular topic these days that a long introduction is probably unnecessary, so this introduction will be fairly brief.

The primary terms to concern yourself with at this point are:

- CLASS

- METHOD

- OBJECT

- INHERITANCE

- MESSAGE

- SELECTOR

To help you visualize the "big picture" of an object oriented system and what the relationships are among all the parts, we'll use an analogy.

Methods and Inheritance

Let's say you want to hire an accountant to prepare your income tax return.

As a class of professionals, all accountants have a certain basic knowledge about accounting and manipulating figures. It is their fundamental job to adhere to generally accepted accounting principles when working on the financial records of a client. The methods they all use include calculating figures, cross-footing entries, checking calculations a second time, placing parentheses around negative numbers in a ledger, and so on.

But within that universe of all accountants, there are specialists. Some devote themselves to corporate tax work, others to accounting for self-employed professionals, such as doctors. No matter what the specialty, each shares the same fundamental knowledge of accounting as their colleagues in other specialties. That is, by virtue of being related to the class of accountants in general, they inherit many of the characteristics of all accountants. Most of their methods may even be the same, such as double-checking figures, using parentheses, and the like. But some of their methods may be different. For example, one kind of accountant may specialize in handling financial records for corporations whose annual sales are in excess of five-million dollars. Another subgroup may do all kinds of accounting work, but its methods involve calculating the final tax form on a computer instead of calculating and writing entries by hand. In the case of each of these subgroups, their predominant methods are the same, but with minor variations in certain methods. Therefore, while each subgroup, or subclass of specialty accountants is a class unto itself, each retains many ties to the larger class of all accountants.

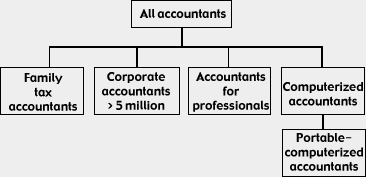

A yet smaller segment of a subclass of accountants, however, can have its own special methods. For example, there could be a small subclass (actually a subclass of a subclass) of computerized accountants who bring a portable computer along and perform the work only at the client's place of business. But even this sub-subclass can trace its methods back through all levels of the class hierarchy, which might look like this:

Objects and Messages

So far, we've been talking only about classes of accountants, not the actual people who do the work. The accountant you select to do your taxes, say his name is John, would fall into one of the subclasses that best meets your particular tax needs.

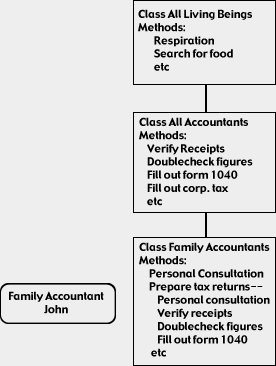

For the sake of this example, Let's say that John is a member of the class of accountants that works with family tax planning and tax return preparation. In other words, John is an "instance", or an actual, physical example (an object) of the class of family tax accountants. When you summon John to do your taxes, he automatically brings with him the ability to perform all the accounting and tax preparation methods that belong to the specialty subclass he belongs to, as well as all the methods he inherits by belonging to a hierarchy of accountant classes. He may not have to summon absolutely every method for your tax job, but they're in his background just the same.

To get John going on your tax return, you give him the appropriate instructions, including all the figures he needs and the final go ahead. In other words, you give him the message, prepare the tax return based on my figures.

When John receives this message, he knows that the figures you provide are the parameters to be passed to the methods he will be using to calculate your taxes. He also knows, according to the methods in his background, that prepare the tax return; means he should do certain things, like organize the figures, obtain copies of each tax form necessary, and so on. The prepare the tax return part of the message is a selector in that it tells John what method (of the many methods in his background) to proceed with first. Even within that very first method he performs, some of the individual steps, such as organizing the figures, may be inherited from the superclass of all accountants. One or more of those steps, however, may be unique to his subclass of family tax preparers.

Now, let's say that at the office you are responsible for hiring an accountant to do the company tax return. Because John is a specialist in family tax planning, you wouldn't want to select him. Instead, you hire Marvin, because he comes from a class of corporate tax accountants.

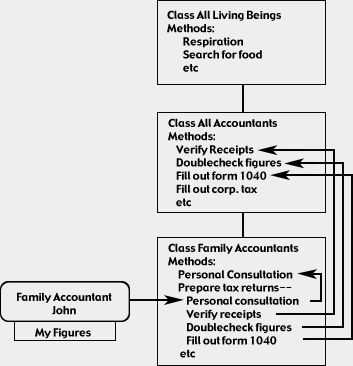

To Marvin, you give almost the same message: prepare the tax return based on the corporate figures. Marvin receives the same message as John, but because the methods in Marvin's class are not identical to John's, a different process takes place in the preparation of the return. Some of Marvin's steps may be the same as John's, because they share the same steps with all accountants, but others will be unique to Marvin's subclass. And the corporate figures you give Marvin, even though many will have the same names as the personal figures (income, medical expenses, tax credits, interest deductions), there will be no confusion between returns. Only your family's figures will be in John's return; only the corporate figures will be in Marvin's. Despite John's and Marvin's common heritage of accounting methods, they work completely independently of each other.

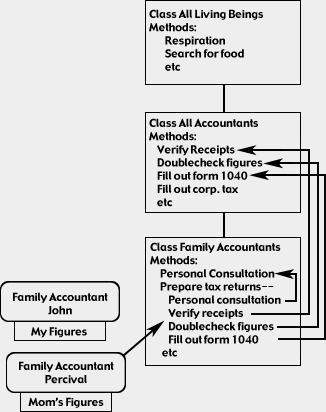

The same would be true if you hired a colleague of John's class to prepare your mother's tax return. If his name is Percival, you can give Percival the same message and your mother's figures, and there would be no interference among the three returns you have in the works.

If this accountant example were a true object oriented system, the class of all accountants would itself be based on another all-encompassing superclass, something like "all living beings". In other words, there must be a primeval class from which all classes are derived, and all the primeval methods apply down the line, as long as they haven't been modified by a subclass. Therefore, even though John doesn't think about it, he breathes, his heart beats regularly, he seeks nutrition periodically, and so on. If you send the message John, hold your breath for 15 seconds, the method for breathing would not be found in either of the accountant classes to which John belongs, but rather in the primeval class of living beings. It's possible, nonetheless, for John to reach back through the hierarchy of classes to that primeval class and make a change to the method that controls his breathing.

Let's take another look at what we've just covered.

Classes and subclasses are defined by the methods that dictate how an object is to behave. A subclass inherits all the methods of its superclass, and adds to (or if necessary, modifies) the superclass' list of methods. An object is a singular instance of a class or subclass. An object is capable of performing all operations specified by methods in its class and its Superclass.

For an object to do any work, it requires that a message be sent to it. The message must contain a selector, which the object matches with one of its possible methods. Any data (parameters) passed to the object inside the message remain the private property of that object (and are not generally accessible from outside the object).

Looking at the following diagram, when we send the message, John, prepare tax return with my figures, John matches the selector prepare tax return with the methods in Class Family Accountants:

This method is, in turn, defined by a method from its own class (e.g., Personal Consultation) and by methods that the subclass inherits from its superclass (e.g., Verify Receipts, Doublecheck Figures, and Fill Out Form 1040).

When you send the same selector to Percival, but with your mother's figures, Percival follows the same procedures as John, but never sees your figures, which John has to himself:

| Lesson 3 | Tutorial | Lesson 5 |

| Documentation | ||