Difference between revisions of "Lesson 19"

(→Drawing Views-the DRAW: method) |

m (8 revisions) |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 04:41, 1 January 2009

Inside the grDemo

Before we begin to explain the inner workings of the graphics demonstration program (grDemo), you should be familiar with its basic operation. First, print out the listing for the 'grDemo' source file, which is located in the Demo folder. You will need to follow along with the source code listing to understand the discussions in this lesson. It will also be helpful if you have handy a printout of the following files: windowMod.txt, window+, ctl, view, scroller and QD.

Next, load and run grDemo to gain an understanding about what it does.

To load grDemo into Mops dictionary, double-click Mops.dic or PowerMops icon to load Mops dictionaly into memory. Then select 'Load...' from the File menu. When the dialog box appears, select grDemo and open it. This file contains Need commands for the files it needs, and these will be loaded automatically. As each file loads, You'll see a message telling you what is being loaded. When all the files are loaded (the File title on the menubar reverts to black on white, and the Mops prompt appears), type go.

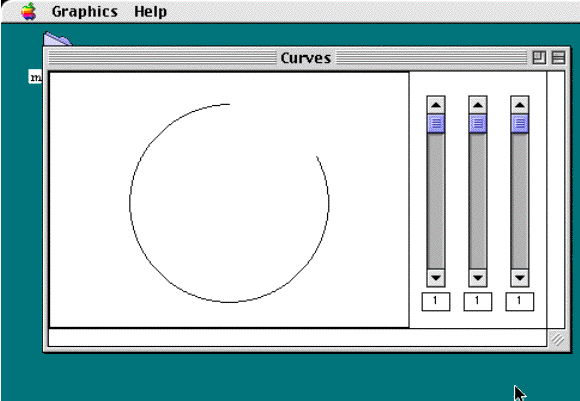

| Now the program (which we'll call 'Curves') will begin. | Experiment by moving the scroll bars and selecting different routines from the Graphics menu. |

As we explain various parts of this program in these final lessons, we will be revealing many of the Macintosh Toolbox features. While this will in no way serve as a substitute for Inside Macintosh, it will nonetheless give you an appreciation for the many options available to you in programming with Mops. You should also see enough here to guide you to designing other applications.

It is important that you understand the desired results of this program before we explain it, just as it is imperative to know what you want a program to do before you begin writing it. This demonstration program contains some simple examples of menus, controls (like scroll bars) and a window with a separate area in which various graphics routines are displayed. The graphics displayed in the window are the ones defined in the Turtle demo, explained in the last few lessons.

If you were designing this program, this would be the time when you ask yourself these two basic questions:

- What kind of objects will be in the program? What classes need to be defined?

- What will be displayed on the screen?

The first question relates more to the inner workings of the program, and the second to the 'human interface' aspects. Of course these two questions are interrelated, but it is often helpful at the start to look at them separately.

In the case of our demo program, the question of the inner working is already largely answered, since we will be using the routines we have developed in the last few lessons. The interface question remains, however, and a lot of work needs to be done here. You'll find, however, that Mops has already taken care of most of the messy details.

Views

When thinking about the appearance of anything on the screen, the Mops class which does most of the hard work is class View. In essence, a View is a rectangular area within a window, which displays something. A window is not itself a view, but a window contains one special view which covers the whole of its area except its title bar. This view is called the ContView of the window (since it covers the whole of the window's contents). Everything else which displays in a window must display in a view.

Class View has a number of features which make it quite easy to set the size and position of views, and control what happens when they are clicked or need to be drawn.

Views are hierarchical. That is, views can (and usually do) belong inside other views. We call a view containing another view a parent view, and the view it contains its child view. If you have done any Newton programming, you'll be familiar with this terminology. In fact, you'll be pleased to know that many of the Mops view features will look rather familiar.

| Let's look again at the Curves window to identify the views controls. | This window has a pane in which the graphics are drawn — clearly this will be a view. There are also the three scroll bars and the digital displays beneath each one. The scroll bars will be views, and the digital displays will also be views. |

Positioning Views

So far so good. Now we also need to look at how these views will be positioned. Clearly the digital display which belongs to each of the scroll bars should stay with its scroll bar, even if we reorganize things so the scroll bars go somewhere else in the window. The simplest way to do this is to create some more views. If both a scroll bar and its digital display are child views of one parent, it becomes easy to move them together. So what we do in the Demo program, is to define three 'indicator' views, where each indicator has a scroll bar and a digital display as its children.

There is one more view, and this is the contView for the window — the view which covers the whole of the window's area.

Thus we have 11 views in all. The contView is at the top level. Then the graphic pane and the three indicators are at the next level”these are the children of the contView. Then each of the three indicators has two children — a scroll bar and a digital display.

The position and size of a view is defined in terms of its bounding rectangle, its viewRect. However in a program you won't normally set the viewRect directly (although you can if you have to). Normally you will specify the four sides of this rectangle relative to the view's parent or siblings, with a range of options, which can be independently set for the four sides.

The measurement option for each side is called its 'justification', and the corresponding number the 'bound'. There are four justification values and four bounds for each view. If a parent view moves or is resized, normally its child views are also moved/resized according to their bounds and justifications.

Again, this scheme will be familiar to Newton programmers. So will most of the justification options we provide, although we do have a few extras. One such extra is that we have four justification values for each view, one for each side, instead of just two (for horizontal and vertical) — this reflects the fact that views are more likely to be resized while a program is running, on a Mac than on a Newton.

Here are the possible justification values (defined as constants):

| Name | Meaning | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| parLeft | parent left | the bound is measured from the left edge of the parent | |

| parRight | parent right | the bound is measured from the right edge of the parent | |

| parCenter | parent center | the bound is measured from the center of the parent | |

| parProp | parent proportional | the 'bound' is a value out of 10000, expressing a proportional distance across the width of the parent. | |

| parTop | parent top | the bound is measured from the top of the parent | |

| parBottom | parent bottom | the bound is measured from the bottom of the parent | |

| ( Note that parCenter and parProp can also be used in the vertical direction, with the obvious meanings.) | |||

| sibling left | sibling left | the bound is measured from the left of the previous sibling | |

| sibRight | sibling right | the bound is measured from the right of the previous sibling | |

| sibTop | sibling Top | the bound is measured from the top of the previous sibling | |

| sibBottom | sibling bottom | the bound is measured from the bottom of the previous sibling | |

| myLeft | my left | (right bound only) — this is measured from the left of this view, so we are directly specifying the width of the view | |

| myTop | my top | (bottom bound only) — this is measured from the top of this view, so we are directly specifying the height of the view | |

The default values are parLeft and parTop, which simply means that the child view's bounds are relative to the top left corner of its parent.

This scheme may look complicated, but is really quite easy to use. In most situations the bounds and justification values can be set up for a view at compile time (via the setJust: and setBounds: messages), and your program won't need to take any other action — the view will keep moving itself automatically to the right position whenever the parent view moves

Let's look at how we've set up these quantities for the views in our grDemo application. Look at the CLASSINIT: method in class Indicator:

:m CLASSINIT:

parCenter parTop parCenter parBottom setJust: theVscroll

-8 0 8 -20 setBounds: theVscroll

parCenter parBottom parCenter parBottom setJust: theReadout

-12 -16 12 0 setBounds: theReadout

classinit: super

;m

Here we position the child views of the Indicator, namely the vertical scroll bar theVscroll, and the box with the digital display, theReadout.

Note that both setJust: and setBounds: methods take four parameters, which are in the usual order left, top, right, bottom.

In the horizontal direction, we want both the child views centered within the Indicator (theReadout will be directly underneath theVscroll). The width of a scroll bar is always 16 pixels, so we set the left and right justification to parCenter, and its horizontal bounds to (-8, 8). Our readout box is going to be 24 pixels wide, so again we set the left and right justification to parCenter, this time with the horizontal bounds (-12, 12).

In the vertical direction, we want the top of the scroll bar to coincide with the top of the Indicator, and the bottom to be a fixed 20 pixels above the bottom of the Indicator, to allow room for the readout box. So we set the top justification to parTop and the top bound to 0, and the bottom justification to parBottom with the bound -20. The readout box will have a fixed height of 16 pixels and always be right at the bottom of the Indicator, so we set both top and bottom justification to parBottom, with the bounds (-16, 0).

If you try resizing the demo window, you'll see the results of these settings. The vertical scroll bars will stretch or shrink according to the height of the window, while the readout boxes will remain at the same size.

We should mention why we put the setting of these values into the CLASSINIT: method of Indicator. It is primarily because theVscroll and theReadout are ivars of Indicator. This strategy makes it easy for us to have more than one Indicator. At the moment we have three, but it would be very easy to have more.

In the case of the graphic display view, dPane, the three indicators themselves, and the contView of the window, dView, we simply declare them in the dictionary. We certainly could have made them ivars of the grWind class, since they really belong to the grWind object. This would have been advantageous if we had a number of grWind objects instead of just one. In our example here, since we have just one grWind object, it is a bit easier to declare the views as normal objects in the dictionary.

This is an example of the kind of tradeoff that will frequently occur in designing a program. In Mops, however, you will find that it is not very difficult to change your design in various ways even after much of the program is written. This is one of the benefits of object-oriented programming.

Since we declared these views in the dictionary, we don't need to set them up in grWind's CLASSINIT: method, and can simply set them up directly at compile time. If you look at the lines where we do this, you should be able to work out how we these views are positioned. We also give some alternative code, commented out. If you use these lines instead, the Indicators will be evenly spaced along the bottom of the window, instead of at the right hand side. Note how we use the parProp justification to achieve the even spacing.

Drawing Views-the DRAW: method

The screen coordinates will have been set so that the top left corner of the view is at (0,0). In Mac terminology, this is called setting the origin to be relative to the view.

- The clip region will have been set to coincide with the view. Thus you can draw outside the view, but anything outside will not appear on the screen. This can simplify things considerably, since you can draw in a view without having to worry about its exact size at that time (and of course its size might change while the program is running).

- Mops has a Rect object, tempRect, which is used for a number of things. When DRAW: is called on a view, tempRect will have been set to coincide with the boundary of the view. This can be very handy. We use this feature in the demo to draw a frame around the graphic, and to draw the readout boxes.

Look at the DRAW: method for class Readout now. Note how we exploit the fact that tempRect is set to the view's boundary, in local coordinates (which are in effect at this point). Here we erase the previous number that was being displayed and draw the box around the view. Next, the 'cursor' where the digits are to be placed is positioned three pixels across and 10 pixels down from the top left corner of the rectangle.

Now the new digits are printed in a field of 3 digits. First we set the set the textmode to 1, the textsize to 9, and the textfont to number 1. Textmode determines how the pen that draws the numbers on the screen will react to the color of the screen below it. With the mode set to 1, the pen draws black on the white background. The textsize number is the actual font size, like the sizes you select in the MacWrite Font menu. The textsize setting of 9 calls for 9-point type.

The textfont number requires a little more explanation. In the Mac Toolbox, fonts are assigned ID numbers.

Some commonly used ones are:

| SystemFont (Chicago) | = | 0 |

| ApplicationFont (Geneva) | = | 1 |

| New York | = | 2 |

| Geneva | = | 3 |

| Monaco | = | 4 |

| Times | = | 20 |

While in this list the application font is the same as Geneva, which is the default, in some programs a special application font is inserted in its place. Since we have not done this, our application font will be Geneva. For the digits in the readout box in grDemo then, the Geneva font was selected. If one wanted to be sure the Geneva font was used, one would use the ID number 3, which is always Geneva.

Now look at the DRAW: method for class Indicator. It gets the current value from the vertical scroll bar, then sends that to the Readout view via Readout's PUT: method. Finally it calls (DRAW): super which does whatever its superclass needs to do for drawing. As we'll see later, we don't use DRAW: super here, because of the other automatic actions such as setting the clip which are done by DRAW:. These actions have already been done for this view, and don't need to be done again. And note that one of the things that we don't need to do again is to call DRAW: on the Readout view, since the Readout is a child view, and it will get a DRAW: automatically.

The three scroll bars are objects of class VScroll, which is a subclass of Control, which is a sub-class of View. Mac controls are drawn by the system. We handle this simply by defining DRAW: for class Control to make the appropriate system call.

The NEW: method in class Indicator is called at run time, when the window containing the view is opened. Here we need to set up which are the child views of this view. This is done with the ADDVIEW: method. We can't do this at compile time, since we have to pass in the address of the child view we're adding, and this might be different in different Mops runs.

| Lesson 18 | Tutorial | Lesson 20 |

| Documentation | ||